It’s late morning on the Outer Banks, a strip of sand that intercepts the Atlantic on behalf of North Carolina, and people are arriving at Oceanas Bistro in pursuit of shade and brunch, in that order. Competition is stiff for the four outside tables the restaurant offers under the wide awning it installed in 2020, specifically to offer socially distanced outdoor dining.

“We get asked a lot about shade,” said assistant manager Susana Sanchez. When, where and how to expand shaded dining with a round of umbrellaed tables is a topic of ongoing debate, she said, as the restaurant strives to keep up with changing public health directives. Meanwhile, hungry diners wait for tables out of the sun.

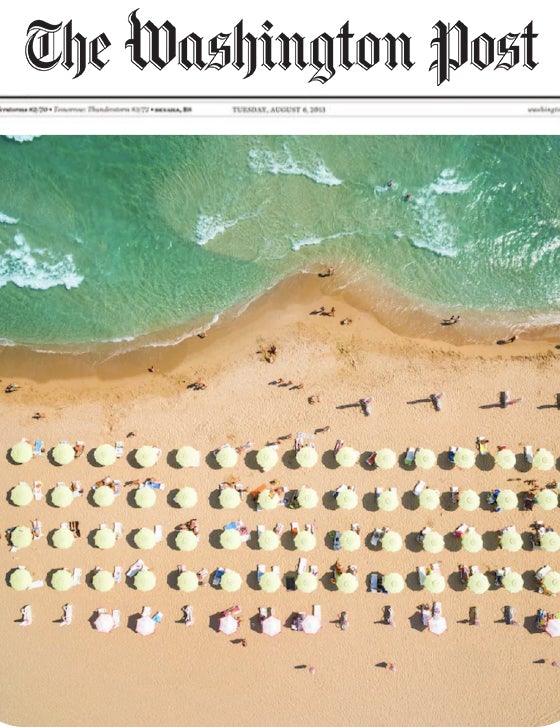

Welcome to summer socialising in 2021, where the most coveted real estate is an isolated spot in the shade.

The millions of Americans who are too young or medically fragile to receive coronavirus vaccines, and those who are vaccinated but want to play it safe, still need open, outdoor spaces for getting together — especially in public venues such as restaurants, event sites, resorts, beaches and parks. Meanwhile, most Americans are acutely aware that they are supposed to avoid direct sunlight to protect themselves from skin cancer.

The two health directives converge under porches, awnings, umbrellas and canopies, where there’s precious little space to accommodate all the sun-averse visitors.

“People are anxious to get out, and it’s going to be a problem. How do you get out safely and keep your distance from people?” said Melissa Piliang, a dermatologist with the Cleveland Clinic.

Damage from sun exposure is cumulative, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation, which means exposure as a child and young adult can emerge decades later as pre-cancer and cancer.

In addition, some chronic diseases and drug regimens, including a few acne-fighting medications and antibiotics, trigger photosensitivity. The Lupus Foundation of America estimates that at least 1.5 million Americans have that autoimmune disease, which invokes a reaction to sunlight.

Anna Chien, a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine dermatologist, wrote a study published May 13 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology that links a greater risk for damage from the sun to a drug — hydrochlorothiazide — used by at least 40 million Americans to control blood pressure. Non-Hispanic Black people, especially women, are most likely to be affected, Chien found. “Given that the medicine does cause sensitivity, they are more prone to develop skin cancer. Knowing that, it’s more important that they protect from the sun,” she said.

Scott LaMont is chief executive of EDSA, a Fort Lauderdale, Fla., landscape architecture firm that finds itself pondering shade in a more deliberate and comprehensive way as hotels, resorts and destinations try to reconcile social distancing with sun protection. Engineering shade is complicated, he said, because the source and power of sunlight shifts by season, time of day and environmental factors, such as adjacent trees. People’s experience of shade is also affected by temperature and air movement; cooling conditions and breeze accentuate the contrast between sun and shade, amplifying comfort.

Last summer, facilities managers realised that to accommodate groups, they couldn’t simply move events completely outside for social distancing. “You can’t have people baking in the sun for eight hours,” LaMont said.

Now, they’re fulfilling the ongoing expectation for sustainably comfortable, socially distanced outdoor gatherings with flexible designs that “blend the outdoor and indoor,” he said, including fold-back glass walls that allow meeting rooms to flow onto adjacent terraces, complete with compatible furnishings.

That’s how Cornelius “Connie” Russell, general manager of the Samoset Resort in Rockport, Maine, is tackling the impending busy season. He’s mapping a tent strategy to create shaded oases on the terrace adjoining the resort’s main dining room, and he’s rethinking how to expand shade at the children’s play area and pool.

Chances are that this year’s shade wars will permanently reframe the amount of structured shade at destinations. “There’s a heightened appreciation for outdoor space that will probably stick around,” LaMont said.

And it’s about time, too, say shade advocates, who want to replace sun worship with shade affection.

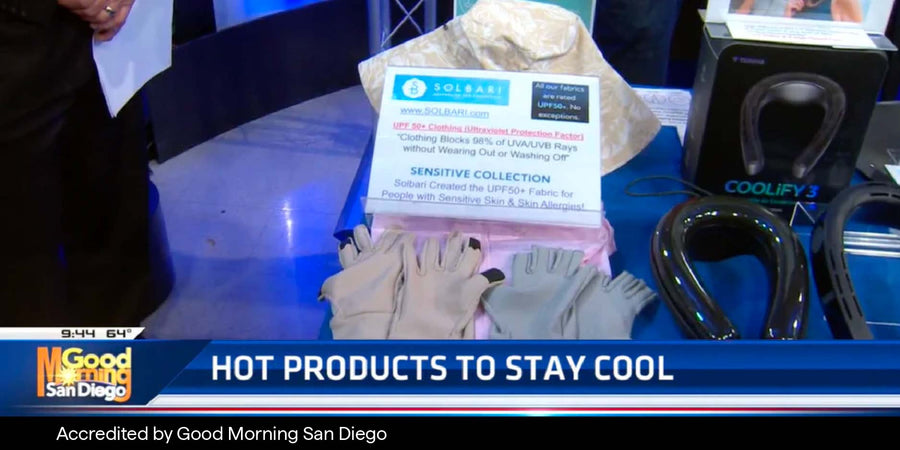

Australians, attuned to seeking shade, have actually adopted local regulations mandating shade in public spaces, said Johanna Young, founder of Melbourne-based company Solbari, which makes and sells clothes and accessories with sun protection. “All shade is not necessarily the same. It’s not just sitting under a tree or under a cabana. There’s reflective UV light that can burn you,” Young said. “The norm here is: ‘No hat, no play.’ ”

That’s the mentality Lurleen Ladd is trying to instill in Central Texas, where her nonprofit, the Shade Project, raises money to install shade structures at schools and parks.

“We have to have more shade in public spaces. Playgrounds, pools that are uncovered, they’re almost unusable without any sort of cover,” said Ladd, who is a skin cancer survivor. “Just staying inside is not a reasonable response during covid, or any time. We want to keep active and to do so safely, avoiding UV exposure.”

Until shade nudges sun out of the spotlight, Americans will have to protect themselves, dermatologists say. Piliang recommended planning ahead to secure structured shade at public parks, restaurants and other destinations. Make the most of reservation options to claim shade shelters or cabanas.

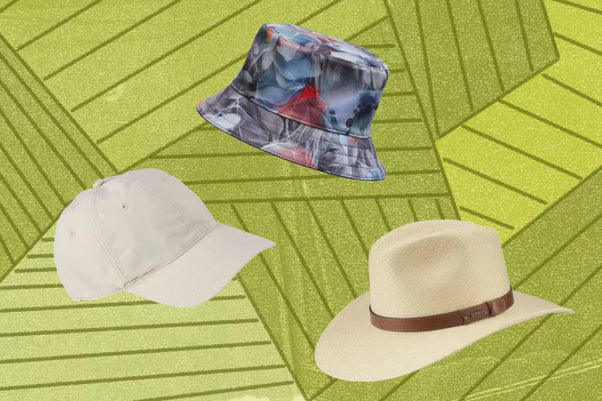

If competition for shade is difficult, bring your own. “Invest in your own shade structure,” said Piliang, who takes a pop-up tent on vacation. Doing so achieves both shade and distancing goals, she said. “When you have your own shade, you can let people in or not.” Large umbrellas made of materials that offer sun protection will cast substantial shade, she said, while tents and cabanas with drop-down walls allow you to capture shade as the sun moves.

Another option is to wear your protection. A layered approach is most reliable: Apply a sunscreen with a high sun protection factor (SPF), put on clothing with a high ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) and spend as much time as possible under a shade shelter. “Even if you’re wearing a hat and protective clothes from sun coming down, the sun bounces off water, and you’re not protected from sun coming up,” said Anne White, chief brand officer of Coolibar, a Minnesota company that designs sun-protective clothing.

Sunscreens and high-UPF clothing work in different ways. Sunscreens keep harmful rays from being absorbed by your skin; sun-protective fabrics prevent UV rays from reaching your skin to begin with.

Sunscreen lotion provides a chemical or physical barrier (depending on the formulation) between your skin and the sun’s rays. The amount of protection is measured by SPF. The higher the SPF, the greater the protection. (It does not increase exponentially; SPF 15 blocks about 93 percent of UVB rays, while SPF 30 blocks about 97 percent.)

It’s important to note that SPF is determined in laboratories and may not be as effective in real life as it rubs, washes or sweats off, dermatologists say; they recommend that an adult use about one ounce of sunscreen every two hours to maintain protection.

SPF standards are set by the Food and Drug Administration, which is engaged in a review of how much SPF and which formulations are the most effective. At the moment, the American Academy of Dermatology advises using a broad-spectrum (meaning it protects against both UVA and UVB rays), water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

The ability of fabric to prevent ultraviolet light from penetrating is measured by its UPF. Manufacturers said they engineer fabrics to be tightly woven; made of combinations of fibers that lock together to block rays; and further solidify the weave with chemical processes. A fabric’s UPF is validated by testing that meets the standards set by independent laboratories.

Because the ray-thwarting characteristics derive from how the fabric is made, the UPF only wears out with the fabric itself. It is not part of a dye or chemical infusion, and it does not wash out, manufacturers said.

The weight, color or weave of an ordinary fabric does not indicate any level of UPF. For instance, said dermatologists and UPF fabric manufacturers, an ordinary microfiber or denim does not offer UV protection, even if it’s black. Always check the labels of clothing, hats and other gear claiming to block the sun’s rays, and confirm the validity of the product’s UPF with a seal from an independent lab.

“There’s likely not going to be enough shade for everybody” this summer, Ladd said. “The best shade you can have is the portable kind: a hat, sunscreen, high-UPF clothes. That was true before covid, and it will be true after covid."